Hey all,

Welcome to Human Nature, the illustrated psychology newsletter.

This week marks the beginning of our new series on developmental psychology. The first years of our lives are instrumental in shaping who we become as adults. Our early experiences, together with our genes and temperament decide how we fare later on in life. But of course, they’re also important in their own right and the study of children’s development is important for guiding parents and helping us understand how we can create societies that better support children.

In this series, rather than give a detailed account of every stage and aspect of child development, which would be a tall order, I will try to answer a few questions that I think have interesting answers to give you a broad picture of developmental psychology.

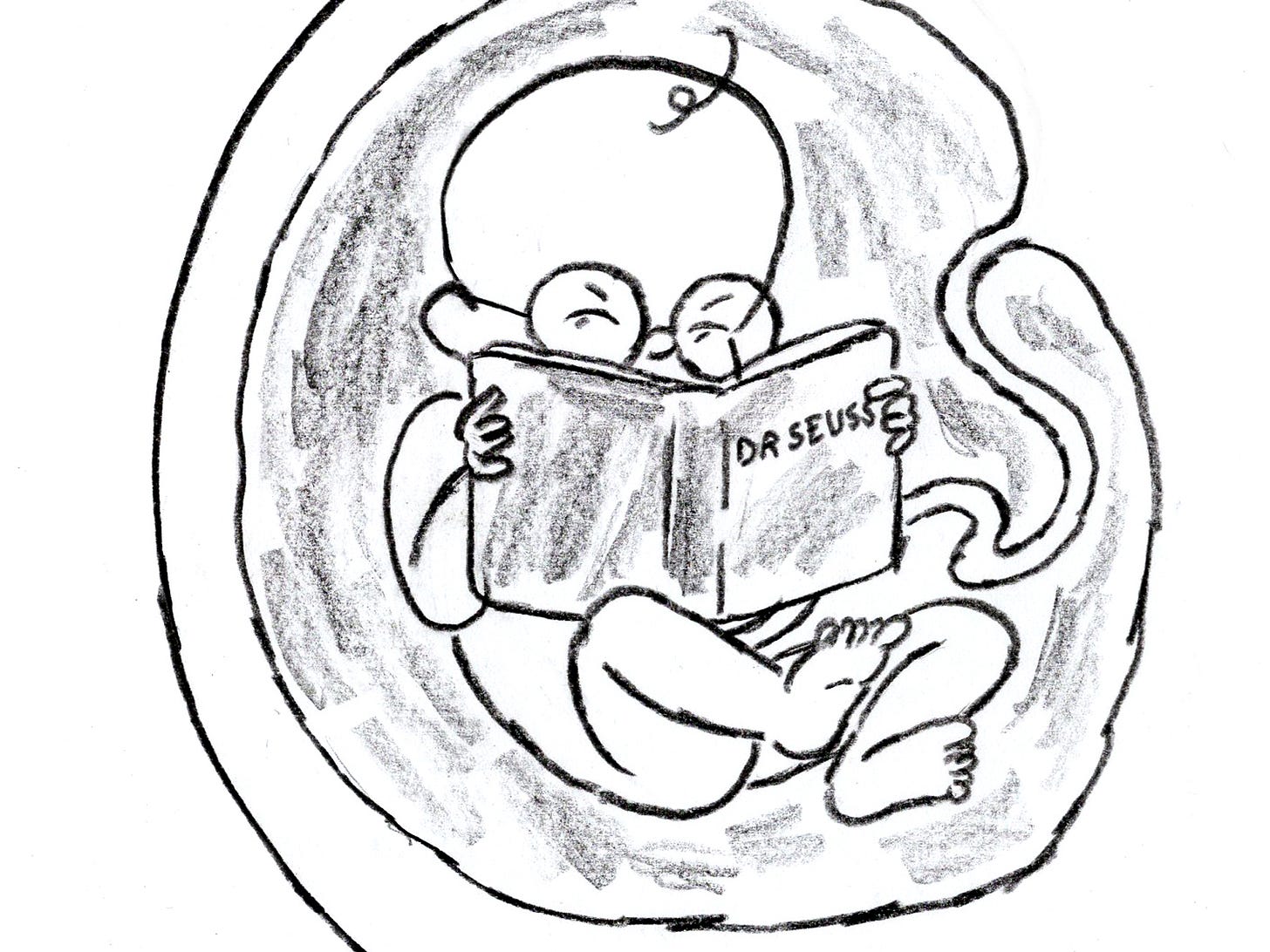

Today’s topic is prenatal learning, or the learning that happens inside the womb.

How much can we learn inside the womb?

One of the biggest questions in developmental psychology for a long time was whether learning begins once we’re born, or if can occur before. We now know that learning starts as early as in the sixth month of the pregnancy, when our central nervous system is developed enough to support it.

A key concept in the study of prenatal learning is habituation. Habituation refers to the decrease in response to a repeated stimulus (Thompson & Spencer, 1966). For example, if you shake a bell next to a baby, they will likely turn their head to look in its direction. Do this enough times, and the head turning will eventually stop. This constitutes a very basic form of learning: as the stimulus is repeated, the infant remembers it and the stimulus loses its novelty.

In a 1995 study, a team of French researchers tested whether habituation occurs whilst in the womb. They played a pair of syllables to foetuses in the 9th month of gestation by putting a speaker against their mothers’ bellies. The syllable pair was “ba-bi”. The first time the syllables were played, the foetus’s heart rate decreased momentarily, a response that indicates interest. But as the foetuses kept hearing the sound, their heart rates returned to normal. The researchers then played the same syllables but in reverse order, this time making the sound “bi-ba”. Once again the foetus’s heart rate decreased, indicating that it was perceived as a new stimulus, and showing that foetuses can differentiate between syllables (Lecanuet et al., 1995).

An earlier study examined whether prenatal learning extends to life after birth. The researchers asked mothers to read aloud from The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss twice a day during the last six weeks of their pregnancy. After the babies were born, the researchers fitted them with tiny headphones and special pacifiers connected to computers. When the babies sucked in a specific pattern, they heard the familiar Dr. Seuss story. But when they sucked in a different pattern, they heard a different, unfamiliar story. The babies quickly reverted to the pattern that played them the Dr. Seuss story, indicating that they recognised it and preferred it to the unfamiliar one (DeCasper & Spence, 1986).

Newborns also show preferences for smells and tastes they experienced whilst in the womb. For example, in one study researchers asked mothers to drink carrot juice four days a week during the last three weeks of their pregnancy (Mennella, Jagnow & Beauchamp, 2001). They found that at about 5 and a half months old, their babies preferred to have their cereal prepared with carrot juice rather than water, showing the persistence of memories made in the womb and offering an explanation to cultural food preferences.

So should parents-to-be put speakers against their pregnant bellies and blast Mozart, or read Dostoyevski aloud everyday? Not really. Although foetuses can perceive sounds and develop certain basic preferences, they won’t be able to understand the meaning of words or retain any factual knowledge. Besides, they will familiarise themselves with the world very quickly after they’re born anyway, so starting education before birth seems a little too early.

Thank you for reading and see you next time.

Sources:

How Children Develop (Robert S. Siegler, Judy S. DeLoache, Nancy Eisenberg, 2010).

Human Fetal Auditory Perception. (Lecanuet, Granier-Deferre & Busnel, 1995).

Prenatal and Postnatal Flavor Learning by Human Infants. (Mennella, Jagnow & Beauchamp, 2001).

Haha glad you noticed!

That Dr. Seuss detail is everything